X-ray Laser Pulses in Two Colors

SLAC researchers have demonstrated for the first time how to produce pairs of X-ray laser pulses in slightly different wavelengths, or colors, with finely adjustable intervals between them – a feat that will allow them to watch molecular motion as it unfolds and explore other ultrafast processes.

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

SLAC researchers have demonstrated for the first time how to produce pairs of X-ray laser pulses in slightly different wavelengths, or colors, with finely adjustable intervals between them – a feat that will allow them to watch molecular motion as it unfolds and explore other ultrafast processes.

This technique, reported March 25 in Physical Review Letters, could open up a new realm of experiments at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), potentially revealing how bonds between atoms form, break and rearrange and how atoms absorb light on ultrafast time scales of less than 25 femtoseconds, or quadrillionths of a second. Each of the paired X-ray laser pulses can be tuned to study a specific element in atomic detail, and they can be timed to hit a sample nearly simultaneously.

"The LCLS really is evolving faster than the science can keep up," said Ryan Coffee, one of the lead authors on the paper. "This really showcases its amazing flexibility."

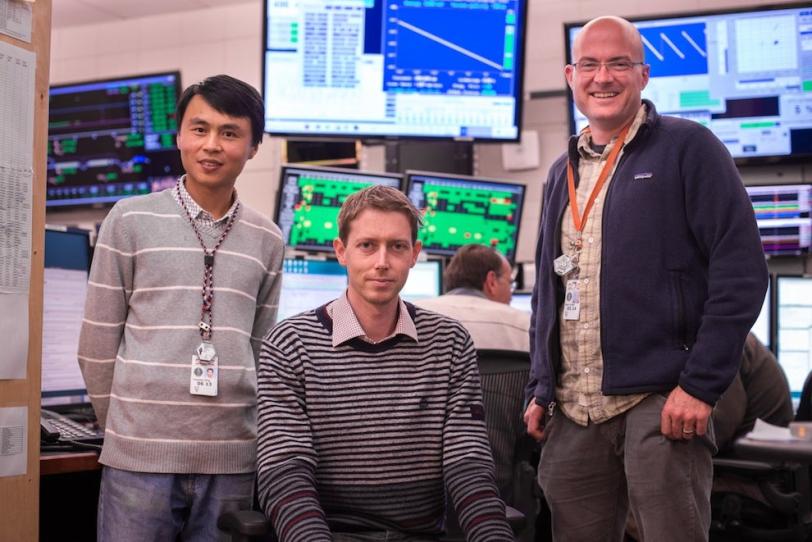

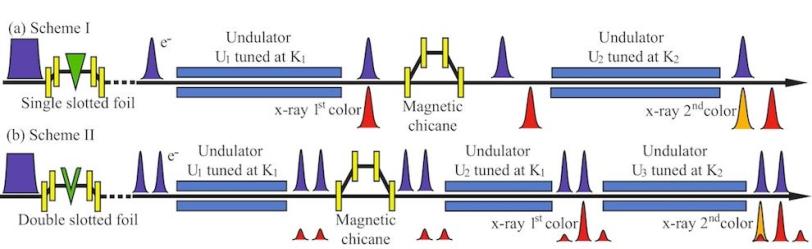

To create the pairs of colored pulses, a team led by Alberto Lutman and Yuantao Ding used two separate sets of undulators – devices that produce powerful alternating magnetic fields. The undulators "wiggle" electrons produced in SLAC's linear accelerator to produce X-ray pulses. Researchers tuned the two sets of undulators to different strengths to produce pulses of different colors, and then used another device, called a magnetic chicane, to fine-tune the interval between pulses.

“This combination of undulators and chicane provides nearly full control of the color separation, as well as of the time delay between colors,” said Lutman.

Ding said, “We have focused on lower-energy X-ray laser pulses, but this technique can be applied immediately to higher-energy X-rays as well,” adding that he hopes requests from scientists who use the LCLS will motivate further studies. Currently, the undulators at LCLS can achieve 2 percent color separation, but new undulators planned for LCLS-II could allow greater color separation between the pulses, expanding the types of experiments that will benefit from this technique.

Already, other teams of scientists at the LCLS have found ways to split the beam of X-ray laser pulses for simultaneous delivery to separate experiments, as well as improve the peak power and wavelength precision of higher-energy X-ray pulses with a technique called "self-seeding."

The two-color pulses can be used in "pump-probe" experiments at the LCLS, in which an initial pulse "pumps" or drives a sample into a desired state and a second pulse explores that state an instant later.

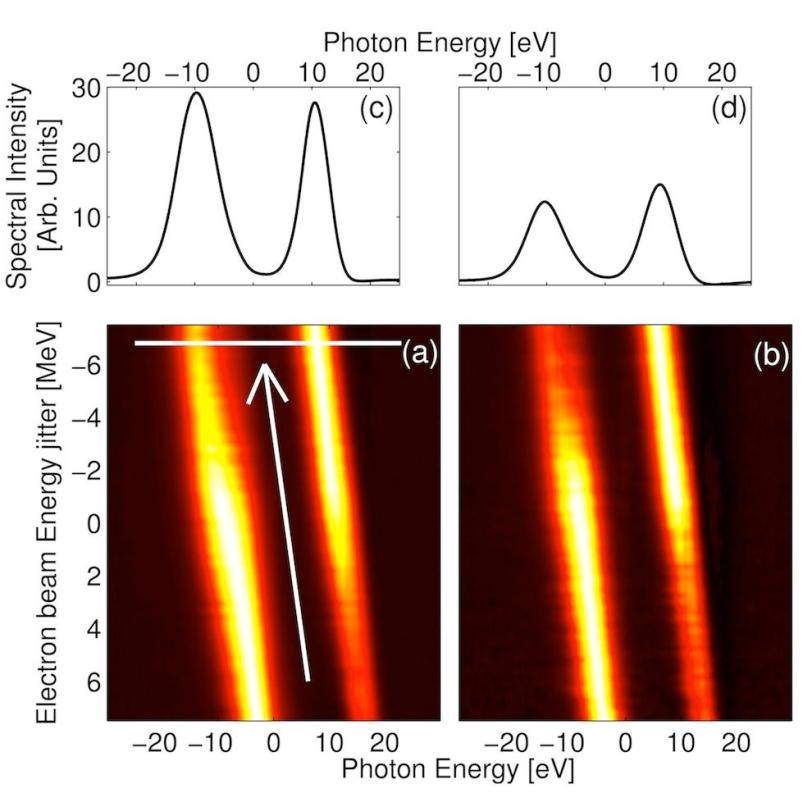

Most of the time the first pulse is from a conventional optical laser and the second one from the LCLS. But in the case of two-color experiments, both are from the LCLS X-ray laser. The two-color method produces X-ray pulses just a few femtoseconds long that arrive at the sample nearly simultaneously or up to 40 femtoseconds apart.

Two Color FEL Operation

(At left: This image of a fluorescent screen shows two X-ray colors separated by a dark central band. The wavelengths of the two colors jitter in unison, jumping up and down together while maintaining a constant separation. In this case, the pulses were separated by about 5 femtoseconds, or 5 quadrillionths of a second.)

Although the wavelengths of the two pulses are only slightly different, they can affect elements within a material in different ways, so scientists can tune them to generate specific chemical reactions. Researchers could even study different atoms within a molecule at slightly different times, providing a precise gauge of chemical and electronic changes within the molecule.

Focusing both pulses on a sample within 10 femtoseconds of each other is especially interesting for some experiments, Coffee said. "You can see how electronic states actually reshuffle themselves, how a bond is broken," he said.

Earlier this month, Coffee led a research team that employed this two-color technique in an "in-house" experiment – part of an allotment of experimental time given to LCLS scientists to carry out high-risk experiments which often result in techniques that can be used by the wider LCLS community. That experiment focused on oxygen, a simple molecule that sets the stage for studies of larger, more complex molecules.

Besides the two-color technique described in the latest publication, an additional method that simultaneously generates the two colors was also used in the oxygen experiment and had been proposed just weeks earlier by SLAC's Agostino Marinelli, Juhao Wu and Claudio Pellegrini.

"This is an excellent example of how a close collaboration between the photon and the accelerator sides of SLAC can push the machine into uncharted territory,” said Zhirong Huang, an associate professor of Photon Science and Particle Physics and Astrophysics who participated in the research. "Our goal is to make all two-color techniques readily available to LCLS users who request them."

The research detailed in Physical Review Letters was led by Lutman, Coffee, Ding and Huang, with Jacek Krzywinski, Timothy Maxwell, Marc Messerschmidt and Heinz-Dieter Nuhn as co-authors.

Citation: A.A. Lutman et al., Physical Review Letters, 25 March 2013 (10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.134801).

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.